Time for the sequel, this course keeps reminding me what college could have been, I wish we had this and not just some dumb stuff to memorize just to pass exams

We ended part 1 with the building out the hardware for our computer and also managed to write a low level language that can run instructions on top the our hardware, Now we move on to ze software and we start with the overview

- Think of something cool

- We write a program in a high level language

- Compiler compiles high level code to an intermediatory VM code

- VM translator converts it to assembly code

- Yoo now we can run this on our hardware

We missed the OS, this is gonna be used by our high level lang for doing stuff like graphics, IO from files, reading keyboard input, Storing objects, threads and so much more that we as programmers dont have to worry about… mostly

Virtual Machines

http://otfried.org/courses/cs492fall2017/slides-vm-to-hack.pdf

The problem with building compilers for high level language to machine language is that different machines have different architecture and hence would need a different compiler, which sucks.

An alternative/ better approach is “Write one Run Anywhere”

For example Java compiles to Bytecode (VM code) that inturn runs with the help of JVM (java virtual machine) on different kinda hardware and ensures interoperability. This idea is called 2 tier compilation and was actually conceptualized by Turing

For our VM implementation we are gonna use the stack machine, which is nothing but an abstraction that consists of a stack and a set of operations we can apply to this architecture

Stack Machine:

A stack is a basic data structure that can be logically thought of as a linear structure represented by a real physical stack or pile, a structure where insertion and deletion of items takes place at one end called top of the stack and also stack pointer.

We have two major stack operations:

-

Push x: Moves the value from memory location x to the stack pointer

-

Pop y: Moved the value from the stack pointer to the memory location y

Using this we also perform arithmetic operations on the stack, like add and sub

| Stack => ADD | Stack => NEG | Stack |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 3 | 10 | -10 |

| 7 |

- Pop argument(s) from stack

- Compute f on the stack

- Pushed the result back to the stack

So these are all part of the abstraction and happen on the stack automatically

But But Why are we doing all this ? (We look at the big picture)

x = 17 + 19 in a high level language gets compiled to

push 17

push 19

add

pop x

Yay stack machine, here are the list of all the Arithmetic and Logical commands

| Command | Return value | Return Type |

|---|---|---|

| Add | x+y | Integer |

| Sub | x-y | Integer |

| Neg | -y | Integer |

| eq | x==0 | Boolean |

| gt | x > y | Boolean |

| lt | y < x | Boolean |

| and | x and y | Boolean |

| or | x or y | Boolean |

| not | not y | Boolean |

This is super powerful cause any arithmetic or logical operation can be expressed and evaluated by applying some sequence of the above operations on a stack

This was demonstrated on stage by David Beazley the “Jimi Hendrix” of live coding https://youtu.be/VUT386_GKI8?t=128

Memory Segments

High level code has different types of variables, we can have static vars, local vars, arguments and so on. To preserve these roles we use memory segments which are just stacks and once we have these segments in place, the compiler can map the variables of the high level on these segments.

Syntax: Push/Pop segment i eg: push local 17

We have 8 mem segments: local, argument, this, that, constant, static, pointer, temp

Note: You cannot pop a constant

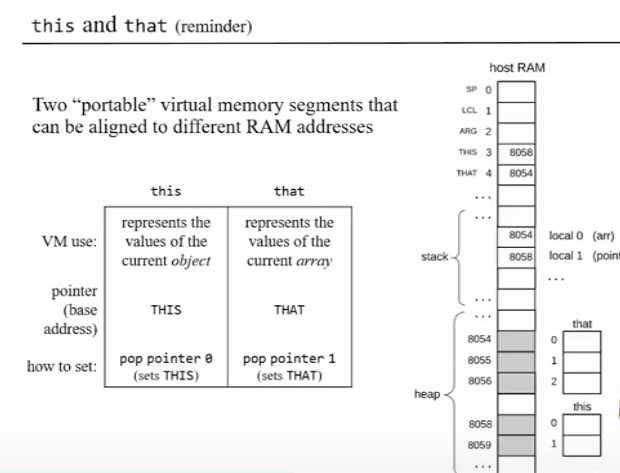

local,argument,this,that: these method-level segments are mapped in an area called “heap”. The base addresses of these segments are kept in RAM addresses LCL, ARG, THIS, and THAT. Access to the i-th entry of any of these segments is implemented by accessing RAM[segmentBase + i]

Theory is all good but how do achieve this, so let’s refresh pointers

| RAM | Memory |

|---|---|

| 22 | 256 |

| 31 | 257 |

| 200 | 258 |

| 28 | 259 |

p1 = 256

p1 = p1 + 3

*p1 = *p1 + 3

p2 = p1 - 2

p1--

*(p2 + 1) = *p1 + *p2

What will be the value of RAM[258] following the code execution?

p1 = 256 // p1 = 256

p1 = 259 // p1 = p1 + 3

RAM[259] = 31 // *p1 = *p1 + 3

p2 = 257 // p2 = p1 - 2

p1 = 258 // p1--

RAM[258] = RAM[257] + RAM[258] // *p1 + *p2

=> 231

So now to push something to a stack we have to do two things, assign the pushed value to SP’s memory location following which we increment the stack pointer.

# VM CODE

PUSH CONSTANT 17

|| VM Translator ||

# Assembly

*SP = 17

SP++

A VM translator is a program that translates VM code to machine language

In our RAM we have a stack pointer and a Base Address that points to a memory segment depending on the type of segment

for example if our base address is 5 for temp memory segment, then

push temp i => addr = 5+i, *SP = *addr, SP++

pop temp i => addr = 5+i, SP-- , *addr = *SP

This and That memory segments represent the current object and the current array that the method in a high level language maybe processing. We keep the base addresses of this and that in the pointer memory segment

Push/ Pop pointer 0/1 pointer can be either 0 or 1 (A fixed 1 place segment)

-

Accessing 0 should result in accessing THIS

-

Accessing 1 should result in accessing THAT

Branching

Now we come to functions and loops, two very powerful high level programming concepts

Todo understand this a low level we divide branching into conditonal and unconditional

-

goto label // Jump to execute command just after label

-

if-goto label // cond = pop; if cond jump to execute command just after label

-

label label // label declaration

With our VM language we have two types of functions

-

Primitive Functions like

addandsubthat are already defined, so we can just calladd -

Abstract Functions that we call from somewhere, In our case we call the OS for math.multiply with

call Math.multiplythese have the same look and feel of a primitive function and makes our vm lang extensible

https://www.coursera.org/learn/nand2tetris2/lecture/R5080/unit-2-3-functions-abstraction 12:10

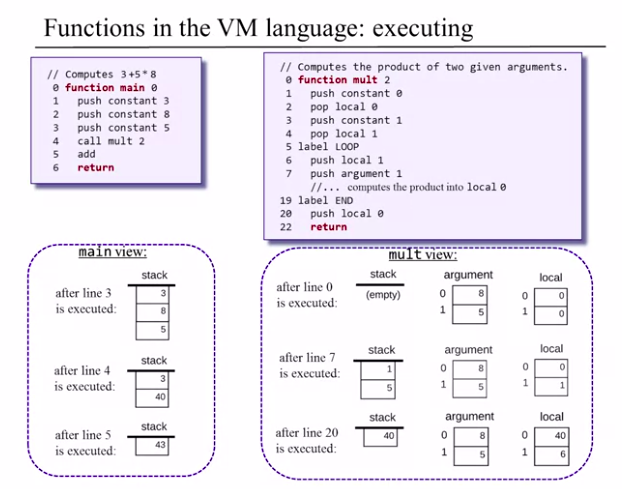

We call mult 2 to denote the number of arguments and function mult 2 to represent the number of local vars. Return pushes the topmost local var back to the stack before popping the arguments

Every VM function has a private set of 5 memory segments (local, argument, this, that, pointer) These resources exist as long as the function is running.

Implementing function call and return

Functions have callers and returns, callers can be chained for eg: a function can call another function which can call call another function and so on, the return of the previous function goes in as the argument. These recursive calling and returning is a LIFO activity and so are such a good usecase for stacks. Once the functions runs and returns its local values are garbage collected to keep a clean slate and if the function used too many local vars in in memory such that the stack can’t handle any more recursive function we get an overflow error, in any high level lang. Functions always returns something even void functions (Push something to the stack), the caller can choose to ignore these like in the case of void functions.

High Level Language

So in this module we learn about jack a general object oriented high level language based on java, It is almost a refreshed on every GENERIC_LANGUAGE101 course I took in college. Jack works with classes, there is a Main class that has a main() method which is where the execution of every jack program begins. We can instantiate an instance of a class as an object using a constructor, call methods defined in the class using the object and maybe even pass it to functions defined outside the class.

Suppose we have an class c = Test() and we call this method c.cry() now this method takes this object as a parameter into its execution but it has no context on c so it gets around this by using the keyword this which will always represent the current object being operated to be used by methods and constructors

The Jack language operates on basic data types like int, float, char etc and even a collection of data types like a list, list is defined as an atom or null followed by the list (it do be highly recursive ngl)

null = ()

(5,null) = (5)

(3,(5,null)) = (3,5)

(2,3(3,(5,null))) = (2,3,5)

List is a single object of linked memory resources (Linked list)

Jack relies on OS to expose much of its APIs just like other languages, for instance Math is can be class we import and use which is actually exposed by the OS, we also have other interactions like reading from the keyboard and writing to the display. Also jack is not a strongly typed language and has methods that can directly alter memory addresses in the RAM (lil dangerous)

Compiler Time

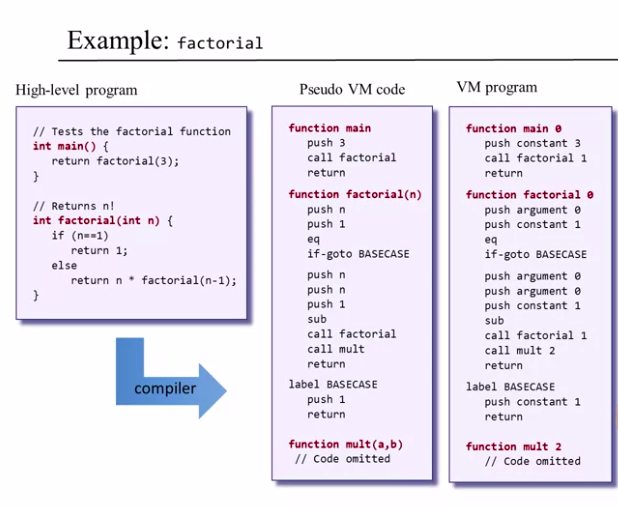

This module are gonna build a compiler that translates our high level language to a low level language, this process is made of two well-defined and more or less independent stages, syntax analysis, and code generation.

Syntax Analysis:

In most modern programming languages, we follow the two tier compilation. For instance in Java the high level code is compiled to Bytecode (In our case VM code) which is then VM translator converts to machine code that actually runs and does all the magix.

The syntax analyzer is made up of two components, a tokenizer and a parser, we are gonna start with the tokenizer or the lexical analyzer which considers any program you write as just a stream of characters.

if (x>0) {

// some useless comment

let sign = "negative";

}

tokenizing

===============> <start> if ( x < 0 ) { let sign = "negative" ; } <end>

So it groups the code to the stream of tokens, removing whitespace comments and keeping only what’s necessary. Tokens are a string of characters that have meaning. For example when you have x++ in may an incremenent in some language or raise an exception in other, A tokenizer must be aware of this and must document allowable tokens in its specification. In jack we have 5 tokens

- Keywords

(Class | constructor | function | method | char | let... etc) - Symbols

{ | } | & | = | ~ | ; | +... etc - Integers

A decimal in range 0 32767 - Strings

A seq of unicode characters including double quotes or newline - Identifiers

seq of alphanumeric characters or an underscore character used to represent var, funcs, arrays , unions etc, identifiers are user defined

Tokenizer can use this knowledge to handle our programs stream of tokens.

eg: When we pass let sign = "negative"; to our tokenizer we will get

</keyword> let </keyword>

</identifier> sign </identifier>

</symbol> = </symbol>

</stringConstant> negative </stringConstant>

</symbol> ; </symbol>

Now we have tokens, that does not we know what those means. The order of tokens are rather the Grammar is really important to understand how tokens can be combined to create valid language contructs

Similar to english grammar we have jack grammar (* means one or more and ? is optional)

for example letStatement varName '=' expression ';' covers let x = 100;

and when the grammar does not match we throw a SyntaxError

Note: let x = y = 5; is also valid since “y = 5” is interpreted as an expression

When you deal with a compiler, the input must match the grammar perfectly. And if there’s any discrepancy, the compiler will raise its hands and say, we have a syntax error and you have to fix your program.

After making sure that our tokens are sane we conform it to a parse tree, for example the statement count+1

parses to a tree that looks kinda like this

|=======> term ====> count

expression----|==================> +

|=======> term ====> 1

The same parse tree can be represented in XML

<expression>

<term>

<identifier> count </identifier>

</term>

<symbol> + </symbol>

<term>

<integerConstant> 1 </integerConstant>

</term>

</expression>

Now how do I construct this parse tree ? how to get from count + 1 to this xml file

class CompilationEngine{

// Parses the tokens using these methods (rules) to an XML file

compileStatements(){

/*

One or more statement

ifStatement | letStatement | whileStatement

letStatement: 'let' varName'='expression';'

expression: term(op term)?

expression is a term with an optional op followed by term

op: '+' | '-' | '*' | '=' | '>' | '<'

*/

}

compileIfStatement(){

/*

'if' '(' expression ')'

'{' statements '}'

*/

}

compileWhileStatement(){

/*

'while' '(' expression ')'

'{' statements '}'

*/

}

compileTerm(){

/* term is varName | constant

varName: string not beginning with a digit

constant: a decimal number

*/

}

}

What we have build here is an LL(1) parser

LL grammar : can be parsed by a recursive descent parser without backtracking

LL(k) grammar : the parser need to look ahead at most k tokens in order to determine which rule is applicable

Jack is LL(1) since when we look ahead 1 token and see an if or a while and then jump, but when it comes to identifiers and only in that case jack is LL(2) since after we have foo, it can be just foo or maybe an array foo[something] or a method foo.caller(), so we need to look 2 tokens ahead. So we need to evaluate expressions a little carefully while parsing our high level code

We have two types of rules in our language, first are the terminal rules with keywords or symbols, once you see them you terminate your rule eg: <symbol> + </symbol> or <keyword> class </keyword>

We also have non terminating rules which are of two types. The first type includes class declaration, subroutine, if, while and other branching conditions, an expression, term or a list of expressions and so on. So these rules are basically a recursive combination of existing rules and in this case our parser does something like this…

<nonterminal>

Recursive output for the non terminal body

</nonterminal>

Now we also have another type of non terminal rule which does not even make it into the xml for eg: if we have 'let' varname '=' expression ';' then we don’t have a

FYI we are not a full fledged compiler but a minimal one, in our parser we are missing a lot of important components like error handling, sometimes the place where we found the error is not the cause of the actual error. we also need to annotate the source code to indicate where exactly the parsing failed so that a dev can fix it with ease. We are also using top down parsing since our lang is simple but there is also a bottoms up approach with backtracking when dealing with more complex grammars. (LR Parser)

There are also tools like Lex and Yacc that can automate what we just built. Lex will split the source file into tokens and yacc finds the hierarchical structure of the program given a set of rules.

We are now officially done with the first half of our compiler, the Tokenizer and the Parser.

Its now time to the build the full scale Compiler that along with lexical analysis and parsing also converts jack code to an executable VM code. Now to achieve this we need to handle a few things, To be exact we need to handle Variables, Expressions, Flow of control, Objects and Arrays. Let’s go through how we handle each of em.

Handling Variables

So lets start by setting the ground rules, this is what we wanna do

sum = x * (1 + rate)

Suppose we have this expression with these variables, We wanna convert this high level way of handling variables to VM code that works with stacks

push x

push 1

push rate

ADD

MULTIPLY

pop sum

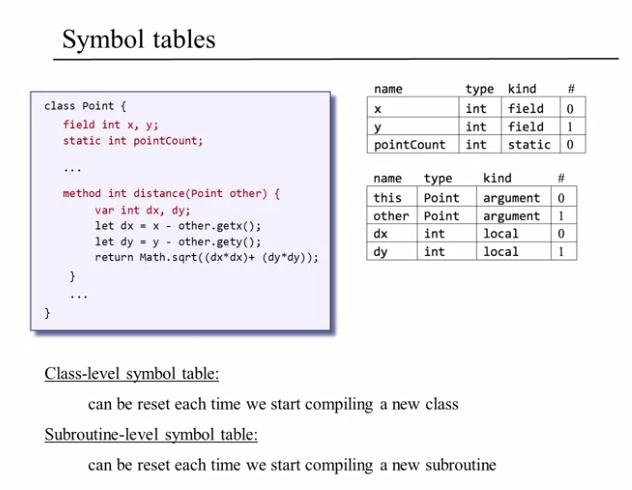

Now to actually do this we need two kinds of information, FIRST we need to know if each variable is a field, local, static or argument. SECOND we need to know if a given variable is the first, second… third variable of it’s kind. With that we can generate the actual VM code.

push argument 2

push constant 1

push static 0

ADD

Call Math.multiply 2

pop local 3

In jack language we have Class level variables ( Field & Static ) and Subroutine level variables (Argument & Local). All these variables have a name (identifier), type (int, char, float, classname), kind (field, local) and scope (class/ subroutine level).

We will handle all this using a construct called Symbol Table

So initially we have the 3 variables in the symbol table with their type and occurrence count. Then we move onto the method, In every method we always operate on the current object and in jack we represent the current object using this and the type is the class name since its called an instance of a class, this an implicit argument that we pass to every method. The other entries of the symbol table are fairly straightforward.

In jack lang, Class and Subroutine level symbol tables can be recycled every time we start compiling a new class/ subroutine

So in the end new variables are added to the symbol tables as they are declared and when a variable is being used eg: let dx = x we lookup the variable at a subroutine level and if not found look it up in the class level symbol tables, If its found awesomesauce otherwise we return the Undefined variable exception when compilation.

In complex high level languages we have the concept of unlimited nesting where we have blocks inside blocks inside blocks (Just imagine I made a recursion joke here) To handle this we represent symbols tables in the form of linked lists,

For variables here, we start the lookup in the scope and move up to the class

[scope 2] ==> [scope 1] ==> [method level] ==> [class level] ==> ||-

Handling Expressions

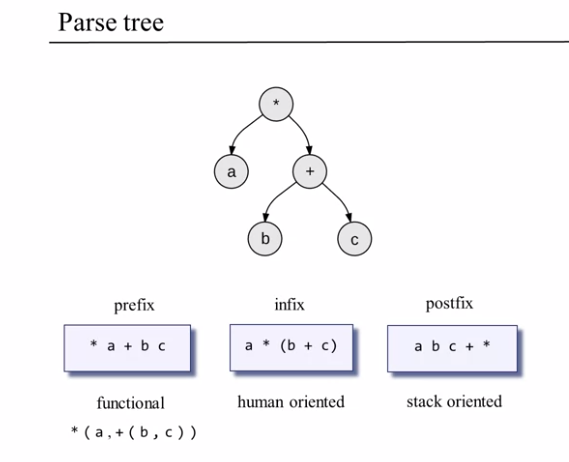

Variables mostly appear in the context of expressions, To handle them we are gonna introduce Parse trees and the different expression notations (Infix, Prefix and Postfix) Ah ! sweet Deja vu

- Infix the notation used in every programming language ever (op between var)

- Prefix is a Functional notation (op before the var) we say

add(a,b)instead ofa+b - Postfix is how stack handles expressions (vars before op)

push a,b,c - add - mult

:: op means operation (add mult) and var means variable (a.b.c) ::

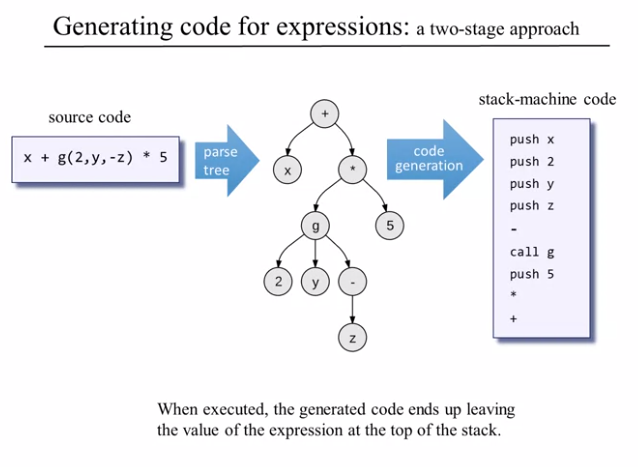

To generate the expression we convert the source code to a parse tree and then into stack code

We convert from parse tree to stack machine code using Depth First Traversal wherein we start at the root + and go all the way to a terminal leaf (Which will be a variable) 2 and process it then we backtrack and traverse recursively until there is nothing to traverse.

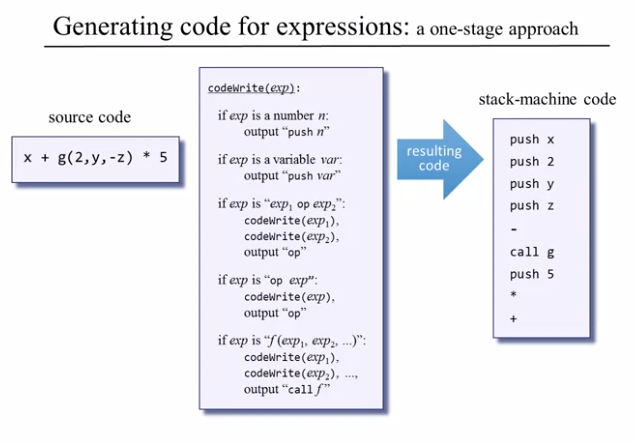

But for a real world program parse tree can be humongous and we don’t wanna traverse all of that, so lets look at alternative approach for the same problem

And yea it is as easy as a bunch of if else statements.

One thing to remember here is when we push a variable say x we don’t just push x but rather we do push local 2 which we get with a quick lookup from the symbol table.

Note: In jack we don’t have operator priority (BODMAS) we evaluate the expression as is and if the user want to follow some algebraic notation they would need to use paranthesis () to explicitly state operator priority.

Handling Flow of Control

In VM lang or kinda in the low level we have 3 commands for flow of control goto, if-goto and label and in high level we have while and if-else

Suppose we have if(exp) { statement1 } else { statement2 } the VM code would be

compiled(exp)

not

if-goto L1

compiled(statement1)

goto L2

label L1

compiled (statement2)

label L2

...

Here these evaluated labels are compiler generated and needs to be unique

While is kinda simpler while (expression) { statements }

label L1

compiled(expression)

not

if-goto L2

compiled(statements)

goto L1

label L2

...

The only thing to note when having nested loops is that Labels should be unique

Handling Objects

On our host RAM we first values act as pointers that denote the current value of the Stack Pointer, Base Address of Local, Arg, This and That segments and all these belong to the VM function currently running.

There is also a location for the global stack, the one that keeps the working stack of the currently running VM function, as well as all the working stacks and memory segments of the functions that wait for the current function to terminate. Namely the functions which are on the calling chain.

When using Local and Arg variables we first put the base address on LCL (first value of the stack) and store the subsequent variables in the global stack.

Object and array data are stored in the heap with pointer references in the stack, lets assume we use pointer 0 (this) and pointer 1 (that) to set the base addresses

// Set RAM[8000] to 17

push 8000 // Set Base address to 8000

pop pointer 0 // Get the Pointer to work direcly on address 8000

push 17 // Push 17 to `this` segment

pop this 0 // Pop the value in pointer (17) to segemnt 8000

// We now have set RAM[8000] as 17

This is the basic technique for accessing object data

push constant 9502

pop pointer 0 // Virtual Pointer to RAM[9502]

push constant 3 // Push 3 to virtual segment for constant

push constant 5 // Push 5

pop this 2 // Pop the value to RAM[9502 + 2] = 5

pop this 1 // RAM[9502 + 1] = 3

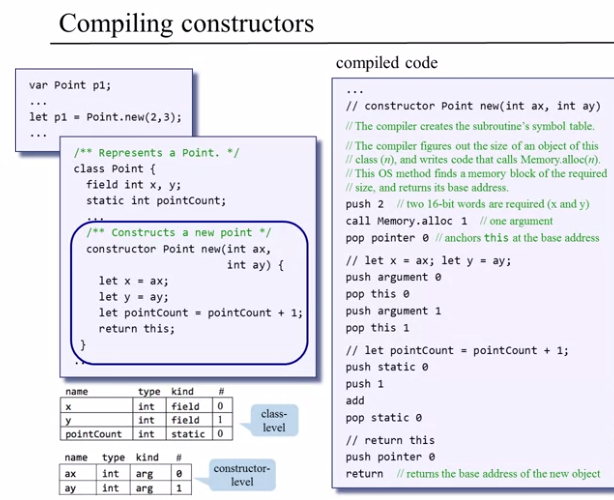

Now lets look at how we handle object construction

var Point p1,p2

var int d

...

let p1 = Point.new(2,3);

let p1 = Point.new(5,7);

Lets look at the low level for a subroutine call

// We have already generated symbol table for p1

push 2

push 3

call Point.new

pop p1 // p1 = base addr of new object

During compile time the compiler maps p1 on local 0, p2 on local 1 and d on local 2. It generates the symbol tables maps them to the RAM and initializes them to 0.

During run time the execution of the constructor code effects the creation of the object on the heap, assignment of base addresses to the previously allocated local 0,1 and 2 locations on the RAM.

So object creation is an operation that spans over compile time and runtime

We discussed compiling calls to constructors and object creation but how do we handle the actual constructor/ Class definition.

The compiler knows that it generates code for a constructor and it knows that the constructor has to create some space on the RAM for the newly constructed object. So how does the compiler know how much space is needed? Well the compiler can consult the class level symbol table and realize that objects of this particular class, of the point class, require two words only, x and y. Because we have a 16-bit machine. Everything is 16-bit. In a more complex language like Java we may need more words. In the case if we have more complex integer types or floating point. But here just by looking at the symbol table we know that we need to secure a memory block that contains two words, Now how do we find such a free memory block on the RAM.

Well, at this stage the operating system comes to the rescue. And the operating system has this functionality called alloc, comes from the word allocate. If you provide alloc with a certain argument like five, then alloc will go to work and it will find a memory block on the RAM which has two important properties. First of all it is five words long. And second of all it’s free. Now no one needs it and therefore the constructor can safely use it.

Object Manipulation

Now we know how to contruct objects, we move onto manipulation

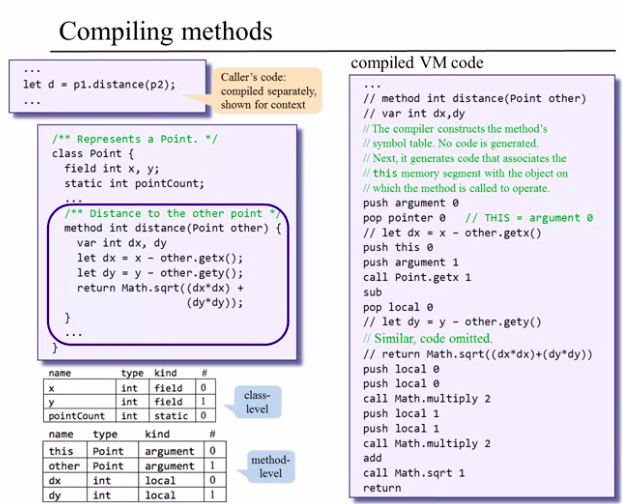

In object oriented languages we have an object that we call a method on and we may or may not pass it args eg: p1.distance(p2) calls distance method in object p1 and passes p2 as arg but in the end we need to convert this OO style code to Procedural code and to do that we pass the object the method is being called on as an implicit argument eg: distance(p1,p2)

So on the caller end of the method the conversion to low level is quite easy, let d = p1.distance(p1)

push p1

push p2

call distance

push d

Now lets see how it is handled in the callee (Where the method called is actually defined)

- First generate the class level and method level symbol table

- We need to work on the current object so we set

this = argument 0 - Now the method needs to execute

let dx = x - other.getx() - Since we are already in the context of the method with

thisobject with the pointer set to the base address, we now just need to push the rest of theargumentsinto the working stack - We need

otherso we check the symbol table andpush argument 1 - After we have everything we

call Point.getx 1notifying the method we pushed 1 arg - Now we push the result to

dxwhich is ref in the symbol table aspop local 0

Void method is just like a regular method but we return no value, eg: there is a print method where we just print the output and no return anything. In these cases we push constant 0 i.e we return a dummy constant 0. Methods always return a value even when they are void.

It’s the work of the caller of this void method to pop temp 0 get rid of the dummy return from stack

Handling Arrays

https://www.coursera.org/learn/nand2tetris2/lecture/lMcUC/unit-5-8-handling-arrays

How do we handle array construction ?

var Array arr;

let arr = Array.new(5);

- First line generates no code, only affects the symbol table. So basically we have local 0 on the stack to represent the arr object

- The second line uses

allocfrom OS to assign memory address8054 - 8058on the heap to the array and local 0 holds the base address (8054), this is just handled like a method

Now that we have constructed the array we move onto the manipulation using this&that

// RAM[8056] = 17

push 8056

pop pointer 1

// We set THAT segment to point to 8056 and

// generate a virtual THAT segment of the stack

push 17

pop that 0

// We push 17 into the THAT stack and pop it to 8056

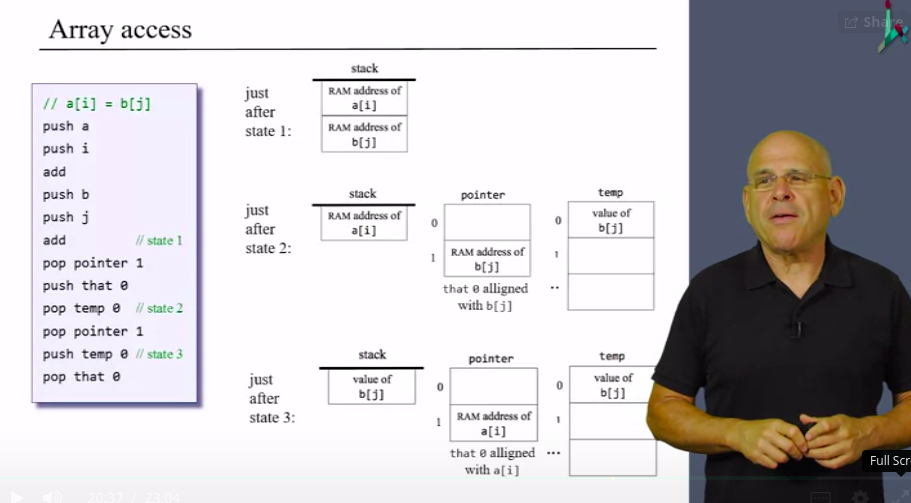

Now this can be generalized to handle array access but there is a bottleneck here, Suppose we need to evaluate a[i] = b[j] if we follow the prev method

// a[i] = b[j]

push a

push i

add

pop pointer 1

// now to b

push b

push j

add

pop pointer 1 // CRASHHHHHHHH

The latter pop is gonna override the address we stored previously so how do we handle that.

We are gonna put one value of b[j] in the temp segment till we pop the RAM address of a[i] on the pointer stack so that 0 is aligned with a[i]

A more generalized expression

// arr[exp1] = exp2

push arr

// VM code for computing and pushing the value of exp1

add // top stack value = RAM addr of arr[exp1]

// VM code for computing and pushing the value of exp2

pop temp 0 // temp 0 = value of exp2

// top of stack value = RAM addr of arr[exp1]

pop pointer 1

push temp 0

pop that 0

A general overview of our compiler https://www.coursera.org/learn/nand2tetris2/lecture/6JxFW/unit-5-9-standard-mapping-over-the-virtual-machine

Syntax Analyzer:_ ===> Symbol Table ===> Code generation

We have now built a simple compiler, if we wanna improve this further we can implement a strong typing system i.e allocate memory based on the type and explicit casting from one type to another. We can also add support for inheritance by looking up the chain of classes during runtime (Late Binding). We also dont have public fields or polymorphism in Jack.

Operating System

An operating system is a collection of software services designed to close gaps between high-level programs and the underlying hardware on which they run.

In particular, operating systems provide numerous low-level services such as accessing the computer’s RAM, keyboard, and screen. In addition, a typical operating systems provides libraries for common mathematical operations, string processing operations, and more.

Modern languages like Java and Python are deployed together with a standard class libraries that implement many such OS services. In this module we’ll develop a basic OS that will be packaged in a similar set of class libraries. The OS will be developed in Jack, using a bootstrapping strategy, similar to how Linux was developed in C.

Math

The Math module of our OS has basic arithmetic operations like multiplication, division, sqrt and so on, so we have Math.multiply(10,21), Math.divide(120,12) these classes are available globally to any jack program running anywhere inside the OS can call these modules.

Memory

The Memory module of the OS provides 4 methods PEEK, POKE, ALLOC AND DEALLOC.

Peek and Poke are used to access memory locations on the RAM. we need this to access our RAM via the abstractions of variables, object and arrays used in high level languages. We also need this to work with IO devices via abstractions like printing something & Reading something and since the memory mappings of these IO devices reside on the RAM we need our OS to bridge this gap.

let x = Memory.peek(19903)x becomes 7 which is present in memory location 19903do Memory.poke(19903,-1)RAM[19903] becomes 11…1 (16 times assuming a 16bit PC)

In High level language we also create tons of objects and arrays that hold references in the stack which point to a memory block in the heap. The challenge here is to allocate this memory and to recycle/ dispose it. To do this we are gonna delve into Heap Management.

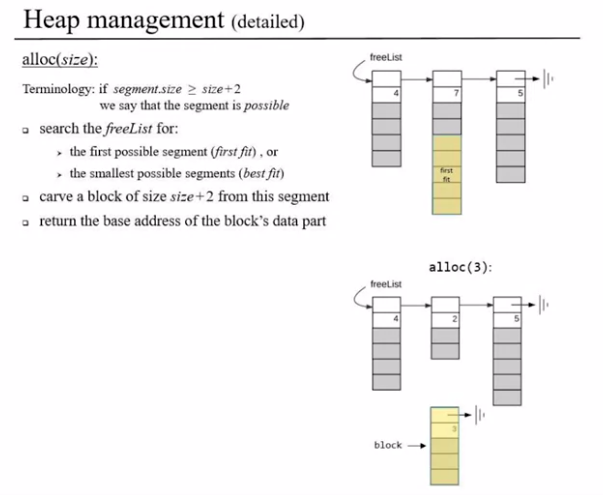

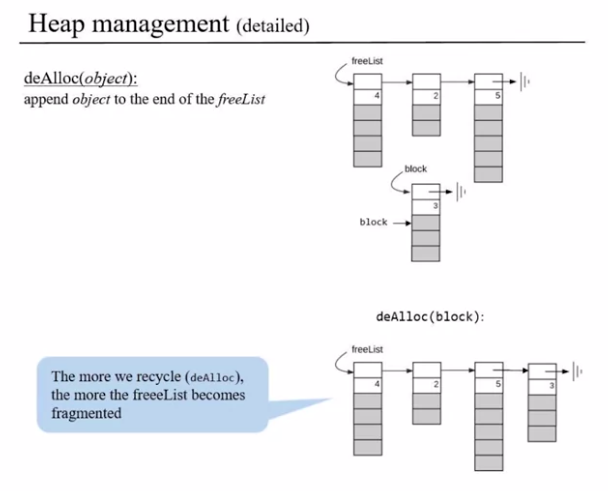

Heap Management https://www.coursera.org/learn/nand2tetris2/lecture/wIMjm/unit-6-5-heap-management

alloc(size)Allocates heap mem of a given size and return a reference to the base addressdeAlloc(object)De-Allocates the given object and frees its space

In languages is java and python we never do a deAlloc cause these languages have garbage collectors which keep track of references to an object made by the high level code and deallocates the object if the reference count becomes zero.

Here is how we manage our Heap with Alloc and DeAlloc

- We split our heap memory into segments and use a linked list to keep track them

- The linked list has a reference to the next segment, the Size of the segment and the actual free segment

- When Allocating we go through segments and allocate segments based on different strategies like first fit (Greedy&Fast) or Best fit (Optimal&Slow)

- DeAlloc appends the acquired segment back the linked list of memory segments

One perk to note here is that when allocating memory often we might tread into a situation where the available most of the memory blocks are smaller and there is no/ few bigger chunk of memory. This phenomenon is called Fragmentation in memory management and it makes alloc harder

There is often a DeFrag method that goes through the whole memory segment and combines these fragmented chunks into bigger ones. We do this when alloc returns empty.

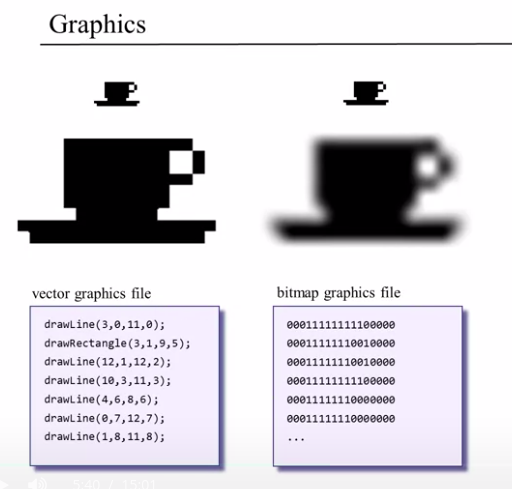

Graphics

Bitmap (or raster) images are stored as a series of tiny dots called pixels. Each pixel is actually a very small square that is assigned a color, and then arranged in a pattern to form the image

Unlike bitmaps, vector images are not based on pixel patterns, but instead use mathematical formulas to draw lines and curves that can be combined to create an image from geometric objects such as circles and polygons

Vector images have some important advantages over bitmap images. Vector images tend to be smaller than bitmap images. That’s because a bitmap image has to store color information for each individual pixel that forms the image. A vector image just has to store the mathematical formulas that make up the image, which take up less space.

Vector images are also more scalable than bitmap images. When a bitmap image is scaled up you begin to see the individual pixels that make up the image

Bitmap formats are best for images that need to have a wide range of color gradations, such as most photographs. Vector formats, on the other hand, are better for images that consist of a few areas of solid color like drawing logos

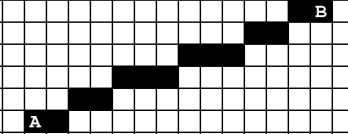

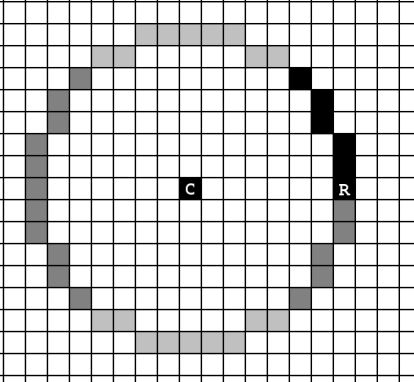

The basic graphic/ primitive operation is Screen.drawPixel(int x, int y) this manipulates the memory mapping of the screen on the RAM ( We have a chubk of 8k registers memory map )

We also have drawLine(x1,y1, x2,y2) and drawCircle(x,y,r) methods

Sys

These are the system methods of the operating system

We start the booting or bootstrapping which usually refers to the process of loading the basic software into the memory of a computer after power-on or general reset, especially the operating system which will then take care of loading other software as needed.

We use Sys.Init and to do this operation we start by calling the init method of every existing OS class, so sys init calls Math.init(), Memory.init() … and so on, after which it calls the main.main() of the jack program

Sys.halt is used to halt a computers execution (Maybe start an infinite loop)

Sys.wait(duration) is used to sleep for sometime

Sys.error throws the errors

We kept the OS abstraction quite minimalistic yet powerful, Some of the stuff we missed are multithreading, multiprocessing, file system, shells, windowing system etc. We also don’t have a GPU to offload graphic operations.

:wq

Leave a Comment